- A Conversation on the History of Hosiery

- Part 1: The History of Hosiery Manufacturing in London

- Part 2: Oral Interviews

- Part 3: Life at Holeproof

- Part 4: Life at London Hosiery Mills

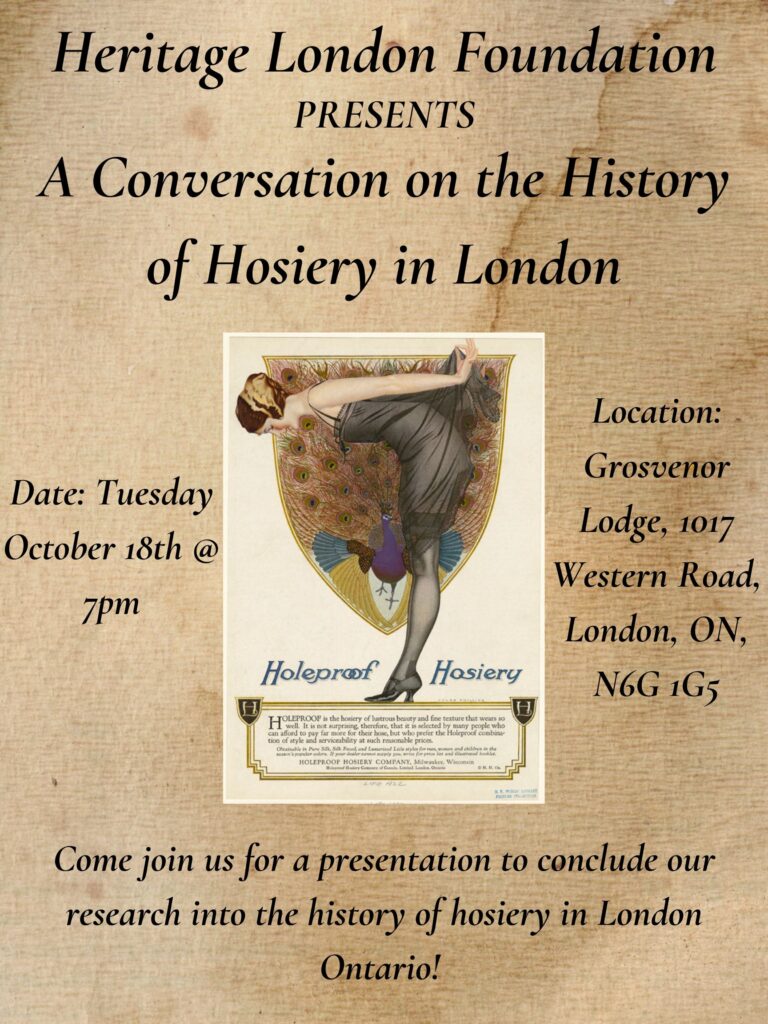

You’re Invited…

Where is Grosvenor Lodge?

Part 1:

Hosiery Manufacturing in London

While London is well-known for some of its successful twentieth century commercial enterprises, ranging from beer and cigars to banking and insurance, it has been forgotten as one of Ontario’s hubs for hosiery manufacturing.

This is the first in a series that will follow the history of hosiery manufacturing in London, Ontario throughout the twentieth century – specifically, the histories of Holeproof Hosiery and London Hosiery Mills.

This series will delve deeply into the story of these two factories, looking into the history of Canadian labour history and individual workers’ experiences. We will also explore the methodology that goes into this type of research – focusing on oral interviews and details about the final product of this research.

Trading Durability for Style

By the 1910s, society was witnessing a shift in standard of living which in turn, impacted fashion. No longer did one have to choose clothing based on warmth and durability but rather comfort and beauty. Further, the shortening of women’s skirts also resulted in a growing desire for more visually appealing stockings. Heavy woolen stockings became a thing of the past as they were replaced with silk and rayon stockings.

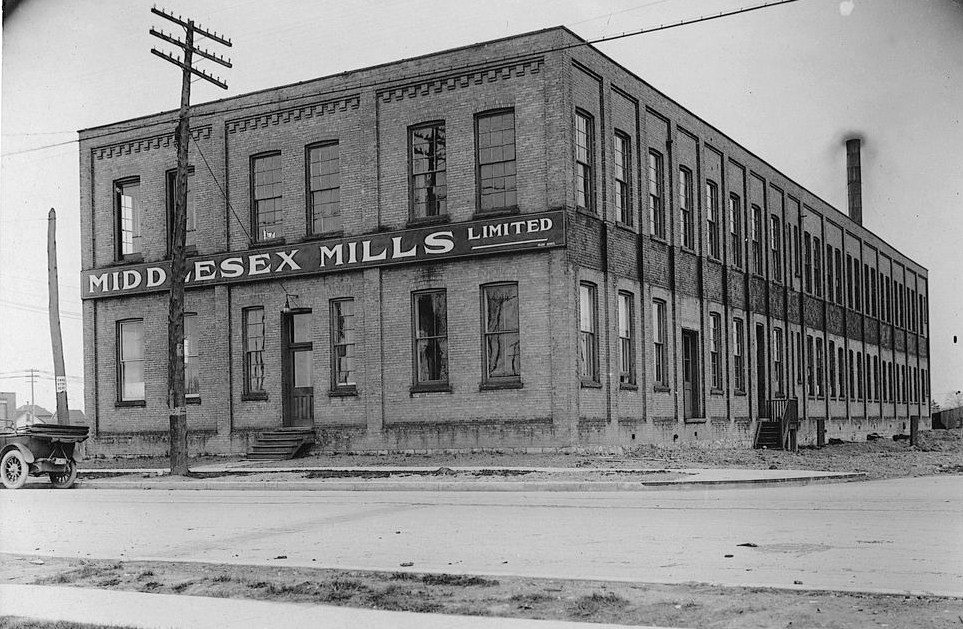

Following this rise in popularity, hosiery factories began to both increase in number and production. By the Second World War, London was home to six independent hosiery factories: Holeproof Hosiery, Penmans, London Hosiery Mills, Supersilk, Middlesex Mills, and Richmond Hosiery.

– Aug 1917 London Free Press via Vintage London, Ontario

Image Source: Western University Archives

At its creation in 1911, Holeproof Hosiery, the first factory of its kind in London, employed only thirty workers. Two decades later, Holeproof and the other new factories employed over eleven hundred people. Around the same time, just London Hosiery Mills alone was producing one hundred and fifty thousand dozen pairs of stockings per year. These companies shipped their product far and wide, from the rest of Canada to as far as New Zealand.

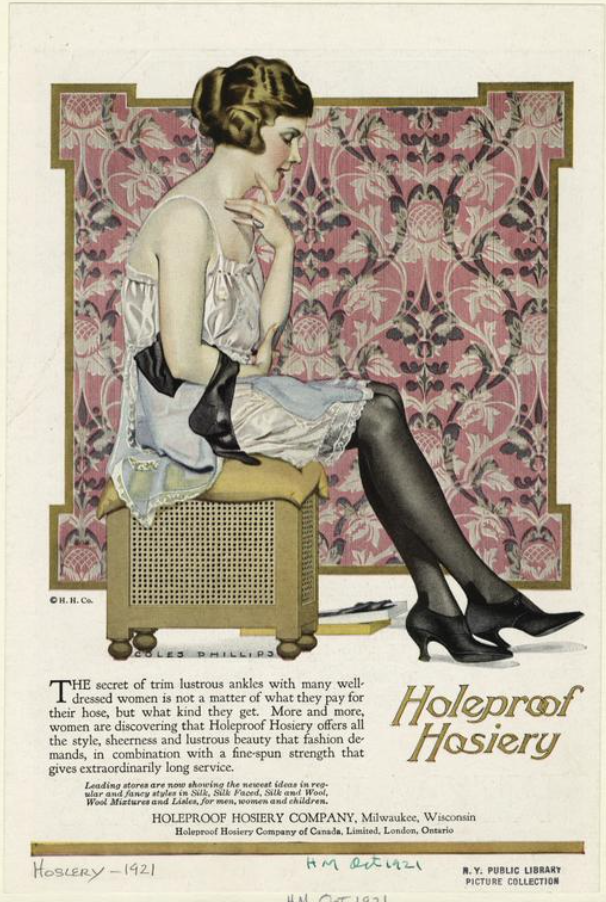

Photo Credit: The New York Public Library Digital Collections

A Female Workforce

Employed within these hosiery factories was a workforce that was predominantly made up of women and girls.

They were responsible for operating various machines, including the ones that completed knitting, countering, and shading, as well as performing hand operations like seaming.

Part 2: Oral Interviews

In 1946, Professor of Psychology at the Illinois Institute of Technology David Boder, travelled to Europe to interview survivors of the war. Afterwards, on the subject of oral interviews he described: “You see that is why I talk to many. This is why I interview many and have them tell their story. So from the little that I get from everyone, the mosaic, a total picture can be assembled. Now you understand my purpose.”

When I was initially developing the topic for this independent research project, I knew I wanted to undertake an aspect of public history that I was very interested in but had never done before: oral histories. I have always been particularly drawn to personal stories as I find that they make history more relatable and understandable.

The importance of conducting oral interviews with women factory workers at these hosiery manufacturers became all the more clear when I began my preliminary research. I quickly discovered that the history of hosiery manufacturing, particularly in Canada, has been massively overlooked by historians. Thus, these oral histories became an even more vital way to preserve an aspect of London’s history.

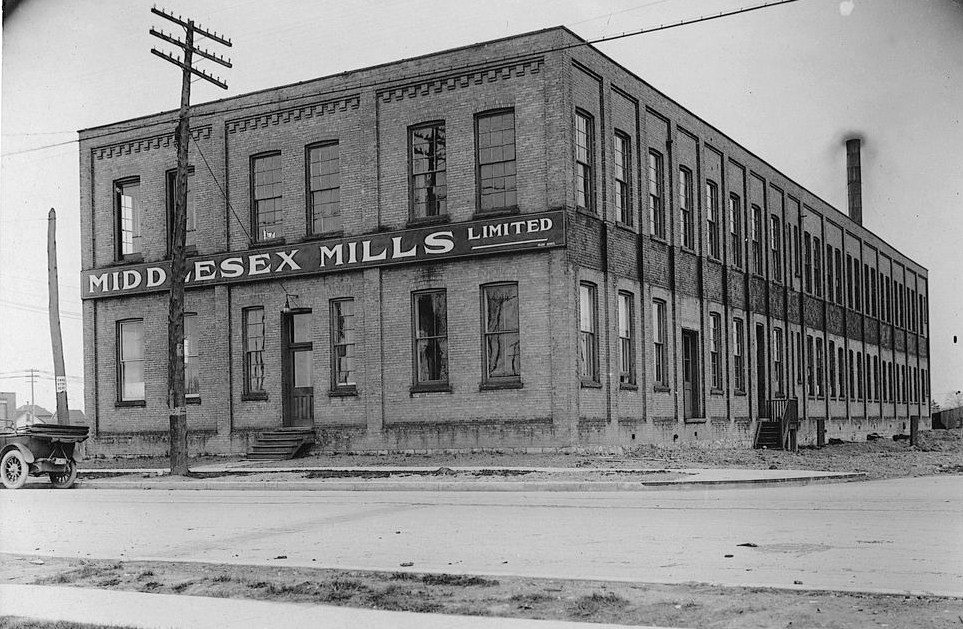

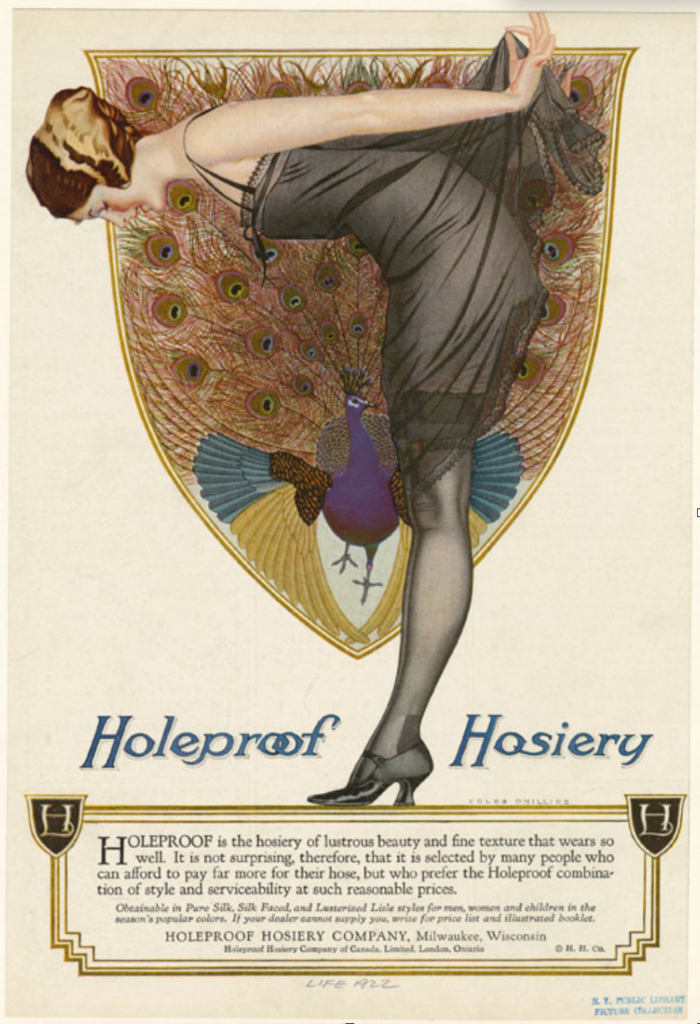

An ad for Holeproof Hosiery published in Harper’s Magazine in 1922. Note the reference to the London, Ontario branch of the company near the bottom of the ad.

Photo Credit: The New York Public Library Digital Collections

However, conducting oral histories is more than just sitting down with someone and asking them questions. There is significant work that leads up to and continues after the interview itself has been completed.

Prior to conducting interviews, the principal investigator (which in this case is me – your author!) must do two main things: research and prepare for the interview. Before anything, the principal investigator must try to educate themselves to the best of their ability on the topic in question. For this project, I did massive amounts of research into hosiery manufacturing generally, trying to find information about the machinery used as well as techniques and specific jobs. I looked at historical documents on pay rates and production rates from hosiery factories and other textile manufacturers in Ontario. I also tried to find as much primary source material on the two companies in question – so that I had a good background on the development of these places.

Next, the principal investigator must take the time to prepare for interviews by creating their interview guide, which includes prompts and questions that they want the narrator’s to hopefully answer. The principal investigator must be familiar with this list of questions and try to get their questions answered but must also be flexible in allowing the narrator to explain things that the investigator did not think to ask. Being good at conducting oral interviews is a skill.

After the interviews have been conducted, the principal investigator must then transcribe each oral interview, so that it can be more accessible in a written form. This process is incredibly time consuming because it is important that the interviews are properly transferred from audio into writing as even the simplest of pauses or “ums” impact the overall feeling of the account. Once the transcriptions are complete the audio records and the written transcriptions should be deposited in an archive (with permission from the narrator) for future use by researchers.

Finally, with interviews done and dusted, I can turn to developing a final product that will share all this glorious primary source material with you, the public. At the time of writing this, prior to conducting most of my interviews, I am still undecided as to what this final product will be. So stay tuned for maybe an exhibit, or a report, or a podcast. Either way, my series will continue to delve into the history of Holeproof and London Hosiery Mills – and will hopefully include some tid-bits of stories from my narrators.

Now you understand my purpose!

Part 3: Life At Holeproof

In my last post, I outlined my approach to gathering the experiences of Londoners who worked at Holeproof Hosiery Company. In this instalment of the History of Hosiery series, I offer you some snippets from those interviews to paint you a picture of life at Holeproof.

“Better Hosiery: The Story of Holeproof”

The Holeproof Hosiery Company was founded by Carl Freschl, a young man who immigrated to the United States in 1872. The idea for the company grew after Carl’s father was sold a loom that failed to produce well-made hosiery, as had been promised.

Carl, frustrated over this failure, began studying and tinkering with the loom until he managed to produce a stocking – it may have been crude and stiff, but it was wearable!

Thus, Carl began a journey to create better hosiery and Holeproof was born in 1886. He moved his growing hosiery company to Milwaukee, Wisconsin and coined the Holeproof guarantee: “six months without holes, or a new pair free.”

The company came to Canada in 1910 when John William Little, obtained the rights to manufacture Holeproof products in London. However, the original company in Milwaukee maintained ownership of a third of the business.

By 1911, the London factory had thirty employees and was making both silk and cotton hosiery. After being in business for just under a decade, the company had grown to include a four-storey structure built at Bathurst and Clarence – where the same building stands today!

In its 1924 advertising booklet, titled “Better Hosiery: The Story of Holeproof,” the company included a drawing of the three Holeproof factories – one of which is the very same Bathurst location. If you’re interested in seeing this document and the picture mentioned, it can be found on page 26 of this document digitized on the Wisconsin Historical Society Website.

A photo of one of the machines inside Holeproof in 1950. One interviewee described how those big windows were often left open and bats would fly around above them as they worked at night.

Source: The London Free Press Collection of Photographic Negatives, 1950-01-13, Archives and Special Collections, Western Libraries, Western University, London, Canada

A Look Inside The Factory

Inside the factory, there was a wide range of machinery and work being done to create the hosiery. There were knitting machines, dying machines, a throwing room, as well as a finishing room.

Margaret Ward, who started working with the knitting machines at nineteen, described for me the work she did:

“There had to be at least… forty… machines that each of us had to… look after and they had… maybe three or four or five big spools of white thread, so if you were inspecting your nylons from each machine, if one had a run in it, you had to stop it [the machine] and get the… repairman to fix it…”

Margaret Ward, Holeproof Hosiery Employee

Another part of her job was to make sure the machines did not run out of thread because “then you had to stop it and we had to put the spool on and then change the… chain belt to put it back in the starting position, so then if you did that you took too long and then you had a bunch of nylons you had to go and inspect.”

Margaret described her work more generally, saying that:

“It was, you were constantly on your feet, up and down, up and down, it was very, very, uh, well… I mean it was just go, go, go.”

Margaret Ward, Holeproof Hosiery Employee

Within the factory, women made up the majority of the workforce. In 1927, sixty percent of this workforce was women. The two employees who I interviewed from Holeproof both agreed that the machinery was run by women, while the repair work was completed by men.

Margaret described how:

“There was no guys that did any of our jobs, they wouldn’t have lasted.”

Margaret Ward, Holeproof Hosiery Employee

“I started at 35 cents an hour”

Women were paid a combination of an hourly wage and by piece work. Trudy Van Buskirk, who worked mostly in the factory office completing orders, started at thirty-five cents an hour. But she admitted how “Eventually, I made 65 or 75… 75 cents an hour.”

On the other hand, Margaret was paid both an hourly rate and piece work on top of that. While she couldn’t remember the exact number, she remembered that “it was a lot less than $1.81 an hour [the amount she made at the job she worked after Holeproof].”

The fact that Margaret was also paid by piece work explains why the work she described above was so urgent – she remembered how:

“… if you… slacked or… let your machines run out of thread and didn’t replace it then it was on you because then you wouldn’t get paid…wouldn’t get the extra.”

Margaret Ward, Holeproof Hosiery Employee

Source: The London Free Press Collection of Photographic Negatives, 1950-01-13, Archives and Special Collections, Western Libraries, Western University, London, Canada

In 1955, the entirety of Holeproof Hosiery (both the London and Milwaukee branch) merged with Julius Kayser & Company and three years later was purchased by Chester H. Roth Company – changing the factory’s name from Holeproof to Kayser-Roth.

The hosiery department at the Bathurst and Clarence plant closed in 1971, coinciding with a remarkable drop in hosiery sales.

The factory closed completely in 1989.

While this blog post aims to be a very brief overview of Holeproof Hosiery, I hope it also highlights the importance of oral interviews and just how much value they can add to understanding our local history.

Part 4: Life at London Hosiery Mills

To conclude this blog series following my research into the history of hosiery manufacturing in London Ontario, I will use my research to paint you another picture – this time of life at London Hosiery Mills.

Established in 1915 by Mr. R. L. Baker, London Hosiery Mills was located just north of the CPR tracks, by the Adelaide Street and York Street intersection. Within the first 30 years of the business, London Hosiery Mills saw massive growth as a company.

By 1938, the company had around three-hundred employees – up from the original twenty – and over three-hundred and fifty knitting machines – up from the original ten.

Inside the Factory

The work being completed inside London Hosiery Mills was practically the same as what women were doing inside Holeproof Hosiery just down the road. The process of creating hosiery was incredibly structured as semi-finished product moved around the factory and through different departments before being ready for sale.

Production began in the knitting room on the third floor, where knitters worked tirelessly to produce well-made hosiery as quickly as possible.

Helen Stoddart, who worked at the mill in the 1950s for almost 7 years, described her chaotic work in the knitting department:

“Because the machines never stopped, the, the stockings were all attached, and they just poured out. As long as you kept the wool going and the needles and everything…They just… spun, spun, spun and you would tear it off, you’d put your hand in it, turn it inside out, throw it over your shoulder…Until you had twelve on your shoulder again – twelve pairs. And then you’d tie them up and uh… that’s what you did…”

Helen Stoddart, Kitting Department Employee at London Hosiery Mills

Once Helen finished with the stockings, they were sent down to the dye house to be coloured. Annecke Soman worked at the mill mostly as a knitter, but she also covered other departments. Between 1976 – 1978, Soman sometimes helped the dyer with his work.

The factory “… just had very large… it looked like a washing machine. But it’s really huge and there would be a certain number of socks and then there’s a recipe for the dyes… to get the different colours and stuff and to do the cycles.”

Annecke Soman, Employee of London Hosiery Mills

The coloured socks then went to the boarding room to be pressed into shape. Virginia Burns worked at London Hosiery Mills in the boarding department for almost ten years, starting in 1976.

Virginia worked on “a machine that had metal… foot and leg shaped sock forms on, on a track… and went into… the machine that steamed them… The steaming was to press them. That’s basically what boarding was, was to press them…”

Virginia Burns, Boarding Room Employee of London Hosiery Mills

Virginia even demonstrated the very precise maneuver that boarders had to learn that allowed them to slip the pressed stocking off the hot metal form in one smooth motion.

The London Free Press Collection of Photographic Negatives, 1948-06-04, Archives and Special Collections, Western Libraries, Western University, London, Canada

Finally, once the socks were boarded – or in other words, put on large square boards after being pressed – they were sent up to the finishing department. Here, some stockings would have their toes and all socks would be stamped with the company name, folded, and placed into the proper packaging.

The London Free Press Collection of Photographic Negatives, 1983-09-09, Archives and Special Collections, Western Libraries, Western University, London, Canada

By the early 1980s, London Hosiery Mills was very noticeably heading towards closure. Ted Collins, a young high school student who worked in maintenance at the factory in summer 1981, described how:

“I’ve been thinking about it – it was clearly end, near the end of the time when I was there. Like you could feel it, right? It like, there were lots of machines that weren’t working, there were lots of… you know, machines that weren’t operating. There weren’t operators for them… it was indicated to me that there were struggles to find mechanics to keep the machines running, to do the knitting.”

Ted Collins, Maintenance Worker at London Hosiery Mills

Only two years later, in 1983, the factory closed as the owners worked to relocate the business to Stratford, Ontario. However, the business closed for good around the same time and the building was eventually demolished in 1987.

After a full summer of work, this fourth and final blog post almost marks the end of my research into the history of hosiery in London. I hope you have enjoyed following along and learning about an aspect of London’s industrial history that has been largely forgotten.

Please stay tuned as there is one more part of this project that is currently being readied for publication!

Back to The Top

Do you have a story to share?

Are you a London local willing to share your stories about Holeproof Hosiery or London Hosiery Mills?

We are specifically interested in stories from women who worked in these hosiery factories. If you have a story, photo, or other artifacts from either factory that you would be willing to share, please email paigem@heritagelondonfoundation.ca.

Our research project, covered by CBC News, aims to preserve the stories of these women in hosiery to avoid losing this unique and critical piece of London history.

Researcher and fourth-year Western University student Paige Milner is tackling the project; you can listen to her full interview on CBC.

Learn More About London Heritage

- New Restorations of the Historic Verandah at Grosvenor Lodge

- 2021 Winners of the London Heritage Awards

- Hadassah: A Part of London’s Jewish Community

- London Locals in History: Elsie Perrin Williams

- Furniture Conservation: Preserving History

- Local Locals in History: Shadrack Martin

- Take a Stroll through Grosvenor Lodge Gardens

- Who is Heritage London Foundation?